Effectiveness of RTI Regimes & Timely Access to Information in the Maldives

Implemented in partnership with Association for Democracy in the Maldives (ADM), this project aims to:

Conduct an assessment of the implementation of the Right to Information in the Maldives

Observe whether the lived experience of information seekers are in line with the goals of the RTI Act

Conduct a review of the RTI Act of Maldives and provide recommendations for future amendments

The RTI Implementation Assessment methodology developed by the Freedom of Information Advocates Network (FOIAnet) to help civil society organisations to assess the extent to which states have implemented SDG Target 16.10 was used to assess the level of RTI Implementation in Maldives. The methodology reviews three areas for RTI implementation and provides a three-point grade of red (weak), yellow (medium) or green (strong) per area in general, for each state institution assessed:

- The extent to which state institutions proactively disclose information;

- The extent to which institutional measures have been put in place to assist with implementation; and

- The extent to which requests for information are being responded to properly

The RTI implementation mechanisms of the following state institutions were assessed for this study:

Overall Analysis

Results of the RTI implementation assessment show that institutions received medium-range scores for both their proactive disclosure obligations and institutional measures enacted for the implementation of the RTI Act. Only one of the ten institutions assessed received a weak score in either of the two areas, which indicate that the level of RTI implementation is not low. However, only two institutions received a strong score in either of the two assessed areas, which indicate a need for improvement as well. The weakest of the three areas was found to be proactive disclosure, which reinforces the findings from ADM’s previous study on proactive disclosure obligations of state institutions. The overall final grade for the assessed institutions was medium, with a score of about 60%. Nevertheless, three of the ten institutes assessed received a strong score, with over 70% being scored by two of them. Steps to enhance the national regulatory frameworks on access to information and the effective implementation of those frameworks as part of member states’ 2030 commitment to the SDGs as prompted by the Intergovernmental Council of the International Programme for the Development of Communication (UNESCO, 2022) are necessary to increase the effectiveness of the national mechanisms in the Maldives.

- The lengthy timelines allocated for state institutions to provide information result in information becoming expired in some instances, such as with media reporting on critical issues or research work with deadlines. It is similarly time-sensitive for civil society designing project proposals, who in the Maldives almost exclusively raise funds through external donors.

- All except one respondent interviewed for this study reported having attempted to obtain information without invoking the RTI regime. Civil society organisations interviewed reported having sought information relating to international obligations of the state, statistical data, policy and implementation, as well as monitoring reports related to government projects. Journalists reported needing information related to current affairs, statistical data and seeking to check facts or updates before publicizing news, and individuals reported seeking information for research or self awareness, for example studies related to vaccination.

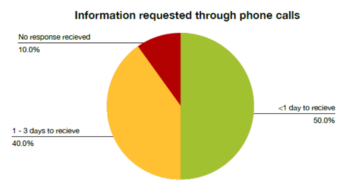

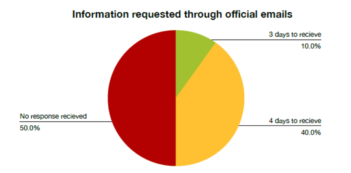

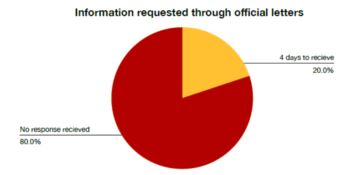

- Two of the respondents said that no response was received to their request at all, while the rest of the respondents did receive a response. Out of those who received a response from the authority where information was requested, 50% reported not having received the required information – out of which 25% are journalists, and 50% said they received the information sometimes. Respondents also reported having to follow up on the request multiple times, at times contacting acquaintances working at the authorities.

- While none of the respondents reported having received full information on time, they reported that often the information was no longer useful by the time it was received. Respondents reported having received (partial) information within three days to two months, which demonstrates that requests for information without invoking the RTI law are not, per say, rejected. However, they are not treated within the principles outlined in the Article 19 of the ICCPR or the RTI Act of the Maldives.

- One respondent reported preferring to rely on information available in the public domain because any attempts to seek information [outside the RTI regime] were either futile or they could not afford the time and chase [within the RTI regime] required. Less than 20% of the respondents reported that in comparison, keeping to the RTI regime provided the assurance that they would receive some kind of response within the allocated timelines, regardless of the lengthy wait.

- Journalists are particularly faced with a challenge in receiving timely information. In a small country with a large rural population, delayed information often means that the media have to move on to other developments taking place around them and cannot afford to wait for weeks or months to bring news to the people. Media interviewed for this study reported not having received adequate information, whether it was requested within or outside the RTI regime.

- Over 90% of the respondents were generally aware of the RTI regime, the obligations of the state and the timelines allocated for provision of information. While over 60% of the respondents have used the RTI regime to seek information, the rest had not. Interestingly, 20% said the risk of not receiving information on time is the reason behind their preference for requests via email and letters, so that there is a possibility of pushing the request through acquaintances, which would not be possible with requests made formally through RTI submissions.

- One respondent stated stigma and fear surrounding RTI requests as the reason for not using the regime and feeling safer with email requests which may prevent sending the institution on “alert” or offending them somehow. This fear corroborates with incidents of threats against information seekers in the Maldives.

- Over 60% of the respondents reported that the timelines allocated for provision of information, including extensions, is too long for the average person to be able to use the information in a timely manner. They also experienced instances where the institution rejected the requests after taking the full length of time, including extensions. Less than 30% of the respondents said that the timelines may be necessary for the state to compile information that is requested for. Some added that this necessity may be true given that information management differs according to institutions and an electronic information management system has not been introduced in the Maldives. Over 40% of the respondents reported that the twenty one days allowed for the provision of requested information is longer than adequate and that the timelines – especially for extensions and the Review Committee stage need to be reviewed and reduced. One respondent said that the RTI regime lacks acknowledgement, and therefore an appropriate process, for those needing information urgently.

- Although over 80% of the respondents faced challenges in procuring the information in full and on time, less than 30% said they pursued the request to the Review Committee and less than 20% reported having pursued a request to the ICOM. The reason others chose not to submit a review request was because it was either too time consuming or they did not have confidence that the result would be different despite the effort, having received similar responses from other institutions as well.

- One respondent said they were repeatedly told by Information Officers that there was a difficulty in providing the information because the documents existed only in paper files. Another respondent said that with most of their requests, the response time was extended by the receiving institution, resulting in having to wait for the maximum allocated time in the RTI law. One respondent reported having had to challenge decisions of the institutions at ICOM in 45% of their RTI requests. One respondent highlighted the recent changes in legislation that bars anyone without a legal practitioner’s license to be able to represent a case at the High Court and the challenges that pose for a regular citizen to appeal a decision of the ICOM at the court.

- Respondents also questioned the need for review committees in the RTI process at all. Since the review committee is tasked with deliberating on complaints submitted regarding decisions made by the Information Officer, on paper it is assumed that none of the members of the review committee will be involved in the decision making regarding information requests prior to that. However, in practice, Information Officers are very rarely able to act with autonomy in making decisions regarding requests for information, most often being unable to provide a response to information requests that have not been approved by a higher ranking official. Moreover since the review committee is required to consist of those at a higher rank than the Information Officer, members of the review committee could very easily influence the decision made in the Information Officer stage. State Institutions that do not have a lot of staff, such as former president’s offices have also expressed that the requirement to set up a review committee consisting of a minimum of 3 high ranking officials as per Subsection 72(e) is a challenge to them.

- Responses received to information requests by respondents to this study, such as extensions of timelines for retrieval of physical documents from old files, indicate the need for basic systems of information management in the Maldives. Apart from the challenges Information Officers face in locating and retrieving those files, a serious risk of damage and destruction of paper files must be considered by the state.

- Respondents appreciated that the existence of the legal provisions protecting and regulating the right to information gives the certainty of a process. While over 90% of the respondents reported having no positive experiences within the RTI regime, others reported having occasionally received the information they needed and on time. Challenges reported by over 90% of the respondents include delay tactics used by some institutions, the lengthy timelines in the law and the technical nature of going through a request for information that feel overwhelming. A clear agreement across all respondents is that the expectation of easy and prompt access to information through the regime has not been met at all.